My first stop in Malaysia was a short visit to the capital city, Kuala Lumpur. And as luck (or the Universe) would have it, this trip just happened to coincide perfectly with a Tamil Hindu festival I hadn’t heard of – Thaipusam! Turns out this one is a pretty big deal in the Hindu calendar, and is also renowned for being a particularly gruesome event. Over the course of the weekend I was fortunate enough to witness devout Hindus going to extreme lengths to demonstrate their faith or to seek favour from Murugan, the Hindu God of War to whom the festival is devoted. The experience was extraordinary to witness, and has given me a bounty of food for thought about the personal choices and sacrifices people make in the name of their faith, and why.

Warning: If you’re of a sensitive disposition, there are some pretty intense (although blood-free) images of facial and body piercing below – proceed at your own risk!

Thaipusam takes place during the full moon of the Tamil month of Thai (January/February). The festival commemorates the occasion when the Hindu Goddess Parvati gave her son Lord Murugan a spear called a vel to vanquish an evil demon, and devotees honour this victory of good against evil by making a pilgrimage to Murugan’s temple in the Batu Caves bearing offerings for the deity. The vel itself plays a central role in the celebrations, with many devotees piercing their tongues or cheeks with a miniature replica of the spear. Pilgrams are also encouraged on their walk with loud chants of “vel, vel” by friends and family along the way.

The festival itself takes place over the course of 3 days, with the pilgrimage starting late at night on the first day, departing from the Sri Maha Mariamman Temple in Central KL (which just so happened to be around the corner from my hotel, in a wonderful stroke of universal synchronicity).

A huge and brightly lit chariot containing a statue of Murugan slowly makes its way from the Temple with crowds of devotees accompanying it on a 15km walk to the Batu Caves. Many of the pilgrims have fasted or abstained from meat for the preceding month, and they walk barefoot to the caves, carrying pots of milk upon their heads. Much of the crowd on that first night were people gathering on the street to witness the chariot’s journey, with a lot of people choosing to make their way to the caves over the following days.

Over the next two days, the spectacle at the Batu Caves was a wonder to behold. I was fortunate enough to meet Shan, a Malay tour guide (off-duty) and Mustafa, a tourist from Syria, on the train heading out to the caves. Shan was a fountain of knowledge about what was going on during the rituals we witnessed, and Mustafa proved to be wonderful company on a day that, strangely, did not attract the large numbers of curious tourists I would have expected.

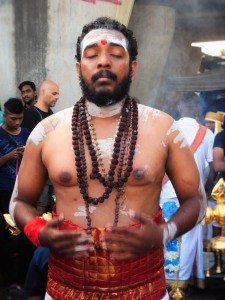

Alighting the train, we were greeted by a scene of bright colours and loud music, as excited Hindus wandered along the many stalls and eateries set up for the festival. We made our way down to the river, which is the focal point for the preparatory ritual before climbing the 272-step route to the temple within the cave. Here, the devotees cleanse themselves of their sins by washing in the river (or in more recent times in the showers that are installed for the event). They then conduct rituals involving fruit and flower offerings, incense, and ritual dance to the deafening sound of drum beats, all with the aim of entering into a trance state, during which one of the Hindu deities is said to possess the body of the devotee, giving him or her the strength required for the next steps in the process.

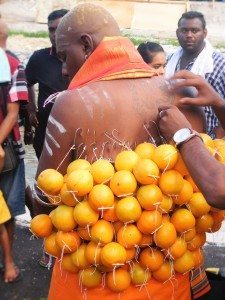

It was fascinating to see different people entering into trance, which happened after holy ash was pressed upon their foreheads to sacred words recited by a holy leader or an elder. Some made the transition quietly, with body trembling and eyes rolling back into their heads. Others had a more intense experience, marked by piercing shrieks or falling to the ground in convulsion. In all cases, after a few moments the devotee had calmed enough to have the miniature vel inserted through their cheeks and/or tongues, or fruits or flowers hung on their backs with individual hooks. Incredibly, despite the grisly nature of the ritual, I didn’t see one drop of blood fall from their wounds. The power given to the devotees by the divine possession is said to prevent any pain being felt or blood flowing from the wounds during infliction. They also gain extra strength to lift enormous kavadis and carry them all the way up the steps into the cave. A kavadi (meaning “burden”) is a large metal-framed structure, often personally designed by the devotee in advance, and decorated with peacock feathers, fruit, flowers, and images of Murugan and other deities.

Once the vels and hooks are in and the kavadi lifted, the kavadi bearers, supported along the way by groups of friends and family, some bearing milk pot offerings of their own, make their way up the 272 steps into the Batu Caves. The staircase itself is flanked by an enormous 140ft golden statue of Lord Murugan, in an gloriously imposing reminder of why we were all here. Everyone is welcome to climb the steps, so myself and Mustafa (Shan had left at this point) started the climb alongside countless yellow-clad determined Hindus bearing their burdens up the final stretch of their pilgrimage. Reaching the top, the entrance to the cave opened out into a vast cavernous space, where the devotees made their way to a shrine to deposit their offerings, pray, and finally take the weight off their shoulders as kavadis and piercings were removed and the devotees came out of trance. Many simply collapsed in exhaustion after an incredibly intense day for all.

The Things We Do…

So why do these devotees put themselves through such an emotionally and physically draining (if not downright painful) experience? Well from what Shan told me, along with what I’ve found online, the precise purpose of undergoing the torture of the Thaipusam ritual varies between participants, but is some combination of atoning for sins, expressing gratitude, fulfilling vows, or praying for some desire to be realised. This variation in motivations left me wondering about the reasons individuals make certain choices in the name of their faith.

Don’t blindly believe what I say. Don’t believe me because others convince you of my words.

Don’t believe anything you see, read, or hear from others, whether of authority, religious teachers or texts.

Don’t rely on logic alone, nor speculation. Don’t infer or be deceived by appearances.

Do not give up your authority and follow blindly the will of others. This way will lead to only delusion.

Find out for yourself what is truth, what is real. Discover that there are virtuous things and there are non-virtuous things. Once you have discovered for yourself give up the bad and embrace the good.

-Buddha (sort of)

I had a thought-provoking conversation with a French-Algerian Muslim yesterday. He is a fun and interesting character who has spent considerable time travelling around the world, meeting people and experiencing different cultures. I was particularly interested in his faith and practices – while he is somewhat of a liberal who, for example, doesn’t believe it is necessary for women to wear a hijab, he is a nevertheless a devout believer who prays and doesn’t consume alcohol or pork. Honing in on the pork question, I asked him what the actual reason is for not eating pork. He didn’t have any real explanation for it, but his reason for abstaining basically came down to “because the Qur’an says so”. This is just one example of the choices made by so many religious folk who adopt a practice essentially just ‘cos someone else said so – rather than taking the standard justification on board, but then looking within to really ask themselves “Does this practice really make sense? Where did the original instruction actually come from? Is it maybe outdated in this day and age?” I have no problem at all with people adopting practices like this under whatever religious faith they ascribe to, as long as the reasoning behind it comes from, or at least resonates with, their own wisdom and common sense.

The Thaipusam ritual practices were very interesting in this regard. One of the things that struck me about the festival was that everyone did things slightly differently. By far most of the attendees I saw over the course of the weekend were just there to walk up the steps and pray. In the “devotee” category, most were just doing the pilgrimage itself, many of those barefoot and/or carrying the pots on their heads, but not all. It was a small proportion who chose to go for the more extreme route of self-mutilation and/or kavadi-bearing, and even within that group the experiences varied, between those who had one relatively small vel through their tongue, versus those who had multiple heavy fruits hooked onto their backs. The size, style and weight of the various kavadis I saw also varied considerably. Moreover, no matter how each person chose to celebrate the occasion, everyone is considered on equal footing, each as individuals on their personal spiritual path; I didn’t notice any competitive behaviour or derisive side-looks in a “my kavadi is bigger than yours” sense, for instance.

Even though the wider philosophy of the Thaipusam festival comes from a more general Tamil Hindu philosophy, it nevertheless showcases the potential for flexibility in a global belief system. Rather than the one-size-fits-all style adopted by so many religious traditions, doesn’t it make more sense to take the underlying philosophy (which is essentially the same across all religions) and adapt your own lifestyle and practice to whatever fits with your own intuition? We all have access to a fountain of spiritual wisdom and logic within, and it is this inner Soul Self that should be heeded when it comes to questions of spiritual practice, more than the centuries-old books we read, or the words of spiritual leaders who may only be unquestioningly repeating what they have heard before. Certainly in my own practice, chanting nam myoho renge kyo has had a profound impact on my life and my understanding of how the universe works, but I have never seen the need for the ritual accessories commonly used by Nichiren Buddhists to supplement the practice. For that is all most rituals and traditions are – supplementary to the core practice of connecting with something bigger. I do sometimes like to use the prayer beads gifted to me when I started chanting. The design of the beads is likened to a human body, and so when you twist the loop and hold the beads, it is symbolic of holding your own life in your hands. This symbolism resonates with me, I like the reminder that I have control over my own life through my thoughts, intentions and actions, and that this practice enables me to better connect with my inner Self. But I know that my practice will still be effective with or without those beads. A lot of similar accessories to a wide range of spiritual practices hold such symbolic meaning – and if that means something to you then by all means go ahead and adopt it. The mistake is when we start believing that the supplemental behaviour is somehow essential to our practice, and that we are somehow doing it wrong if we don’t use the beads, or the vel, or the skull cap.

Spiritual beliefs are an intensely personal matter. Albeit in a rather extreme manner, the Thaipusam festival caters for this individuality in a way that is sorely lacking in most other religious traditions, by allowing each person to immerse themselves as deeply or shallowly as they wish in the ritual practices, without penalty or judgement. All of those pilgrims and devotees ultimately deepen their connection with the divine no matter what method they choose to honour their God(s).

Whatever your faith may be, I would encourage you all to take a good hard look at the practices you undertake in the name of that faith and ask yourself – is this really necessary? Doing something ‘cos everyone else does it, or ‘cos someone said so, doesn’t really add anything to your personal journey and relationship with whatever name you use for All-That-Is. That’s all that really matters at the end of the day – your connection with your Self and with the Universe. Focus on that and do whatever truly resonates in your journey to cultivate that connection – everything else is just noise.

Great post Jessica.

Particularly amused by your reference to the skull cap.

I do however need to raise a point. With the encouragement or lack of discouragement on exercising their faith as you seem to endorse, where is the line? Tempestuous question in the times we find ourselves in, however there are none more pertinent.

I continue to read with pleasure. My interest in worship, sacrifice and cultural practices continues, purely on an anthropological level you understand! I’d like to see you examine/explain in more detail specific reasons for the development of certain rituals. Why 272 steps. Why on that day. What’s the geographical influence of this ritual/ pilgrimage done on this day, in this way in terms of the practice on a wider scale. Community based I expect.

Anyway, keep on keeping on.

Thanks for the comment Mickey! It’s a good question you raise about where the line should be drawn in spiritual practice, especially with all the religious conflict and violence we see around the world. My encouragement of spiritual practice is on a purely personal level – I would never condemn anyone else’s faith or infringe upon someone else’s practice. I think that’s a fair standard we should all hold to, as it is intolerance of others that is the root of so many problems these days, not spiritual belief or practice per se. If your practice strengthens your own connection with whatever name you give the divine forces of the universe, then go for it. But that’s your own individual journey. The guy next to you may be taking a different route, but that’s okay – different strokes and all that.

As for the wider details of the Thaipusam festival, it is a Hindu festival celebrated by the Tamil community, so as far as I know the rituals and celebrations are similar in all locations where there is a significant Tamil population – I only have direct experience of the KL version though so that’s all I can really speak to! The day itself is the day that Lord Murugan defeated the demon with the vel, according to legend at least – you have to remember that Hinduism is the world’s oldest religion and a lot of the festivals and important days are based on ancient legends, so it’s hard to know how the original date was decided upon (although the Gregorian dates are calculated from the Hindu calendar which is based on lunar/solar movements). I don’t think even that level of detail is too important, at least not for the believers themselves – in fact some of the Hindus there told me that the festival celebrates Murugan’s birthday, which is not true. For them, though, their faith and wish to honour their deity is all that is really important. As for the steps, well the Batu Caves are a natural feature in a limestone hill, so I don’t think there’s any significance to the number of steps other than that’s how many they needed to reach the natural cave entrance!

Appreciate the questions! Some of the details above are already mentioned in the original article, and it’s hard to find the right balance (read: word count!) between historical detail and the reporting of what I actually experienced, which is my main goal. These types of posts grow pretty long, pretty fast, so I do tend to sacrifice some of the wider details which can usually be found elsewhere, in favour of my direct experience which is a more unique read. Will definitely keep your feedback in mind though!

Jessica. This is an amazing blog post. Your understanding of the Hindu Festival is incredible and how various rituals can be so important to people in an individualist way. It is encouraging to know that we can follow our own spiritual path in our own personal way in order to connect with, as you so rightly put it, “All-That-Is”. The photographs are incredible.

Thank you for the amazing feedback! So glad the post resonated with you 🙂